Pier Paolo Pasolini had reason to believe that he might be murdered. The gay Italian filmmaker and writer was a breathlessly outspoken critic of Catholicism and his country’s post-war economic boom, an undying champion of the impoverished teenagers and young people that Italy duped with dreams of capitalist abbondanza. He was also hounded by sexual scandals and the ire of political reactionaries. In 1975, weeks before the premiere of his antifascist epic of eroticism and abuse, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, Pasolini was slain on the beach in the Roman district of Ostia. The assailant, a 17-year-old sex worker Pasolini solicited while he cruised town in his Alfa Romeo GT, used the sportscar to run over the 53-year-old after he crushed his testicles with a metal bar.

Pasolini’s 1959 novel, Una Vita Violenta, eerily foreshadowed these events: The book mentions Ostia and features scenes of adolescents who target horny older gay guys for violent robbery. His fellow director Michelangelo Antonioni called him “the victim of his own characters.” In fact, he was probably the victim of a political assassination carried out by a few goons and a scared, blackmailed kid. The trial was a circus; the culprit recanted his confession decades after he finished serving his sentence. Today, it’s widely acknowledged that Pasolini’s prolonged torture and slaughter were premeditated and motivated by grander aims.

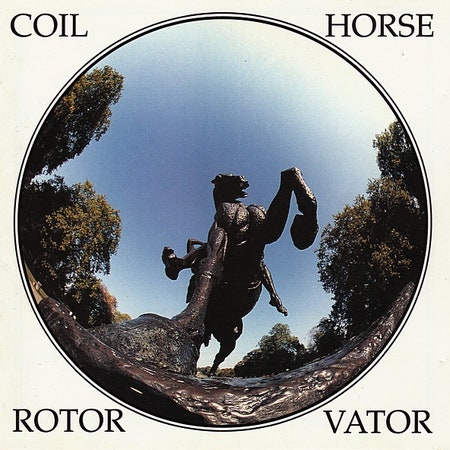

Coil vocalist John Balance pointed toward the cosmic character of this homicide on “Ostia (The Death of Pasolini),” a highlight of his band’s second album, Horse Rotorvator. Balance fixated on the idea that Pasolini anticipated his own demise in his art: Had he come to terms with it, and might he even have wanted to die this way? The song came out in 1986, when AIDS was massacring Balance’s milieu, and he searched for ways to make heads or, more likely, tails of the carnage. “Killed to keep the world turning,” Balance sang in a world-weary croon that seemed to offer Pasolini up to the great churning gears of humankind as it plowed forth at all costs, like the rumbling rotavator of his record’s title.

Coil braid the track with field recordings that Balance’s musical and romantic partner, Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, made at Chichén Itzá, an ancient Mayan city whose inhabitants ritually sacrificed their young. While Coil claimed to resent political music, an activist energy suffused their decision to openly mourn in a society intent on shrinking from disease. Splicing ancient custom and contemporary tragedy, “Ostia” feels like tears poured into civilization’s motor—if the dead were going to be used as fuel, then the grief of the living would give this reckless vehicle some really bad engine problems.